By Cammie McGovern, author

Cammie and Ethan

I got the idea to write a novel featuring a non-verbal character who uses an AAC device in part because I am the parent of a child with autism and I wanted to say something about alternative pathways to communication. I should quickly add, my son does not use an AAC device. He is verbal, but as any parent of a child with autism will tell you—talking isn’t everything when it comes to communication.

Ethan has days when his nonsensical talk seems as if it will—quite literally—never stop.

“YOU MUST BE QUIET!” we yell has he heads into the bathroom for one of his favorite activities—twenty minutes of self-talk in the echo-y chamber of the tile-lined walls. Stand outside the door, as his father and I have done, to listen and piece together clues to his mood, his day, the mystery of his character, and I guarantee you’ll hear nothing that helps you glean any insight. We let him chortle in bathrooms and yell at himself until we quite literally can’t bear it anymore and then, nerves shredded, we beg of him, for the sake of family sanity, to please stop talking. Considering the years we devoted to coaxing language out of him, I recognize the wistful irony to all this.

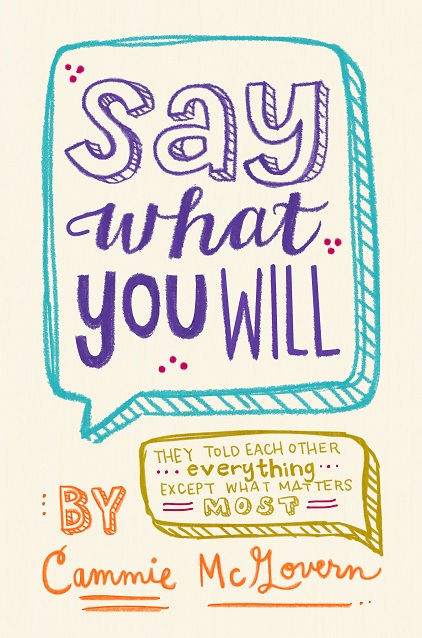

In my novel, SAY WHAT YOU WILL, I wanted to write about a highly intelligent young woman using an AAC speech device in part because I’m interested in the experience of disability, even if the particulars don’t reflect my son’s experience (he is cognitively disabled, as well as autistic.) As a writer for the last thirty years, I’m also interested in language and pathways to communication. I chose to make it a Young Adult novel because I’d long wanted to try writing for younger readers and I remembered being a teen reader myself, falling in love with stories that featured main characters with disabilities (Flowers for Algernon, I Never Promised You a Rose Garden, Tell Me You Love Me, Junie Moon.) Also—perhaps not coincidentally—I started writing it just as Ethan was hitting puberty.

We had long ago adjusted our expectations to the reality of Ethan’s limitations. He is a relatively happy-go-lucky kid who has his passions and delights, few of which involve other people. He loves lawn mowing, watching You Tube videos, and—well, talking to himself in the bathroom. So imagine our surprise when he came home one day and announced that he needed a suit a corsage because he wanted to ask “his girl” to the prom.

What girl? I thought. What prom??

Double that surprise when “his girl” turned out to be Alexandra, a lifelong friend from his Life-Skills class who we’d known since she was a baby. She’s two years younger, has cerebral palsy and twelve years ago, her mother and I were part of a small group of moms who started an organization called Whole Children to run after school, movement-based classes for kids with disabilities. The seed of the idea for Amy, the main character in SAY WHA T YOU WILL, had come to me as I watched little Alexandra, a three-year-old whose parents had been told at birth that she would never walk or talk. Though she was only just beginning to sit up at that point and talking was still a few years away, I remember watching her in our meetings, the way she smiled at all the Moms and laughed when one of us made a joke. She may not have had language at that point, but she communicated beautifully, in a way that made me envious. Then I imagined what her life might be like down the road, as a teenager with a bright, inquisitive mind, trapped inside an uncooperative body.

I also wrote SAY WHAT YOU WILL because I passionately believe we need more stories in books, movies, and on TV featuring characters with disabilities. It is the largest minority population in the US and also the fastest growing, but I would argue it’s also the most underrepresented in popular culture.

The irony of my own family situation is one of the main reasons we need more of these stories. Just as I was writing a story about a character based on his old friend, Alexandra, Ethan came home and told us he wanted to take her to prom. The surprise was not him choosing this person, it was the romantic impulse behind it. Ethan wants a girlfriend? I thought, and got a little teary because the answer is so simple. Of course he does. They all do. One of the biggest surprises we’ve had parenting a child with a severe disability is that once you’ve finally adjusted your expectations to all his limitations, he turns around and surprises us with something that seems remarkably normal. At fourteen, Ethan started asking us for “more privacy please.” At sixteen, he replaced a poster of Harry Potter in his room with one of the Patriot’s cheerleading squad. It isn’t that he’s become a typical teenager, only that he has more in common with typical teenagers than I ever thought possible. We need more stories about teens with disabilities because we need to start imagining fuller lives—complete with love, relationships, passions, and work—so they (and their parents) can start picturing it too.

I would still say that Alexandra communicates far more effectively than my son does. In the back seat of our car driving to prom, he chattered away as she sat quietly, smiling and laughing until we arrived and then her simple directive, “You need to hold my hand, Ethan,” spoke volumes. Even those of us who live with disability every day are learning to understand what our children are trying to tell us. SAY WHAT YOU WILL is one story. I hope in the years to come we have many more…

To read more about the novel and the author you can visit her website. Be sure to enjoy the video on the homepage.

There are no comments yet. Be the first to post!You must be logged in to post.

Communicators In Action